OETC’s Spotlight is a series of stories, interviews and Q&As highlighting news and ideas from across the Northwest EdTech community. Read more stories here.

If it wasn’t for the tree that nearly crushed his truck six years ago, Wallowa County ESD Technology Director Josh Kesecker might never have taken to ham radio.

He was out cutting down trees for firewood, and a close call with one could have rendered his car undrivable.

“‘If I’m out there operating a chainsaw and, heaven forbid, there’s a really bad accident, I’d be unable to get myself help,'” he recalls himself thinking. “There’s no cell phone signal, no 3G, nothing way out in the woods. There’s vast areas of my region where there’s no coverage of anything except maybe satellite.”

Now, Josh has an Extra license, the top licensing class available through the FCC. He’s already achieved his Technician License, which gives access to VHF and UHF bands, and General, which allows him to broadcast on HF band. The Extra License allows an operator to use the entire spectrum of frequencies available to amateur radio, save those reserved for fire and police.

Josh oversees technology for 900 students spread across more than 3,600 square miles. There is no ham radio club in his area; it’s too sparsely populated. But there was another sort of radio community out in the Wallowas, built around a sport most of us never think about.

Ham radio — which doesn’t actually stand for anything; someone said it insultingly in 1909 and then the community embraced it — is often seen as a relic, the dominion of very, very old men who like to recite puns at each other through crackly static. Yet a surprising number of folks in the edtech community embrace it, both as a hobby and a vital tool to keep their schools connected and safe.

Hams frequently make connections with the International Space Station. In fact, if you’re in the right place, you can do that with a five-watt handheld.

Ham radios are curious things. Some look like walkie talkies, others like a cable box, some look like your car stereo if you took it out of the dashboard (because they are in fact designed to be slotted in there, ideally with a big antenna mounted to the roof). You can spend $39 or $2,000 on the radio itself, but then there are also tuning units, power amplifiers, computers that control them via USB. Like so many tech hobbies, it’s easy to find yourself in financial quicksand.

When it’s searching with no information, it makes the same noise as a seashell you hold up to your ear. As you move through the frequencies, you hear chirps one associates with walkie talkies. When you finally hit on something, it might be the bleeps and bloops of Morse Code, people practicing their emergency broadcasting signals, or “rag chewing” (which often is the aforementioned pun-swapping). You can tune in to police, fire and even FAA frequencies, though you cannot speak on them.

You get the longest range when you shoot along the grey line, the edge of encroaching dawn or nightfall that you see on a world clock. It aids in radio propagation because of complicated changes in atmospheric layers; that’s when someone broadcasting from Oregon can hit New Zealand or even Antarctica. Hams have made connections with the International Space Station. In fact, if you’re in the right place, you can do that with a five-watt handheld.

Their terrain is the High Frequency, Very High Frequency, and Ultra High Frequency portions of the spectrum. High frequency wavelengths can be 20, 40, 60 or 160 meters, top to bottom, the height of a rogue wave or a Giant Sequoia or the Space Needle. The larger the height, the further it can travel, which is why ships used to use long-wave radio frequencies.

Ham radio isn’t Josh’s only wavelength work; he’s also dabbled in microwaves — which are in fact part of the radio wave spectrum. They don’t heat the water vapor in the air because they’re dispersed and not bouncing all over each other, like the ones in the metal box on your countertop.

“We built our own microwave radio network in the Wallowa Mountains to bring internet to all of my schools. I have a tower on one of the ridges at 7,000 feet, overlooking the valley. When all the phones are out and the internet is down, my schools can still talk to each other and make phone calls,” he said.

But his main ham activity happens once a year, when he and his son shelter under a canvas tent in the snow to serve as part of the official communications team for Oregon’s only Iditarod-qualifying dogsled race.

Each year, Josh Kesecker mans one of the checkpoints for the Eagle Cap Extreme Sled Dog Race in the Wallowas. As part of the communications team, he ensures communication between all checkpoints, checks in mushers as they pass, and helps dispatch and communicate with Search and Rescue if need be.

“We didn’t have a club like populated areas, but many of the ham radio people would volunteer for this sled dog race, so I said, ‘Sure, I’ll take a shift.’ I never predicted it would be fun, because I wasn’t into sled dog racing at all. I’m an IT guy, not a musher, but it felt great to support others.”

As the manager of the Salt Creek Summit Checkpoint of the Eagle Cap Extreme Sled Dog Race, Josh and his teenage son work together to check in mushers as they go through, coordinate communication between other checkpoints, and deploy search and rescue teams if need be.

“Sometimes the conditions get really bad and our systems that are linked together have problems, so having a skilled radio person in between has been important,” he said, adding that there was in fact a search and rescue needed a few years ago.

Now, Josh is introducing ham radio to the next generation.

“I didn’t realize that my teenager would enjoy it so much. He’s 15 and he’s been doing it for several years — he got his license for the race so he could help me out.”

Josh Kesecker teams up with his 15-year-old son, who has gotten his own ham radio license in order to help with the race.

About 284 miles to the northwest, Highline Public Schools CTO Mark Finstrom is using his Extra License to handle just about any emergency.

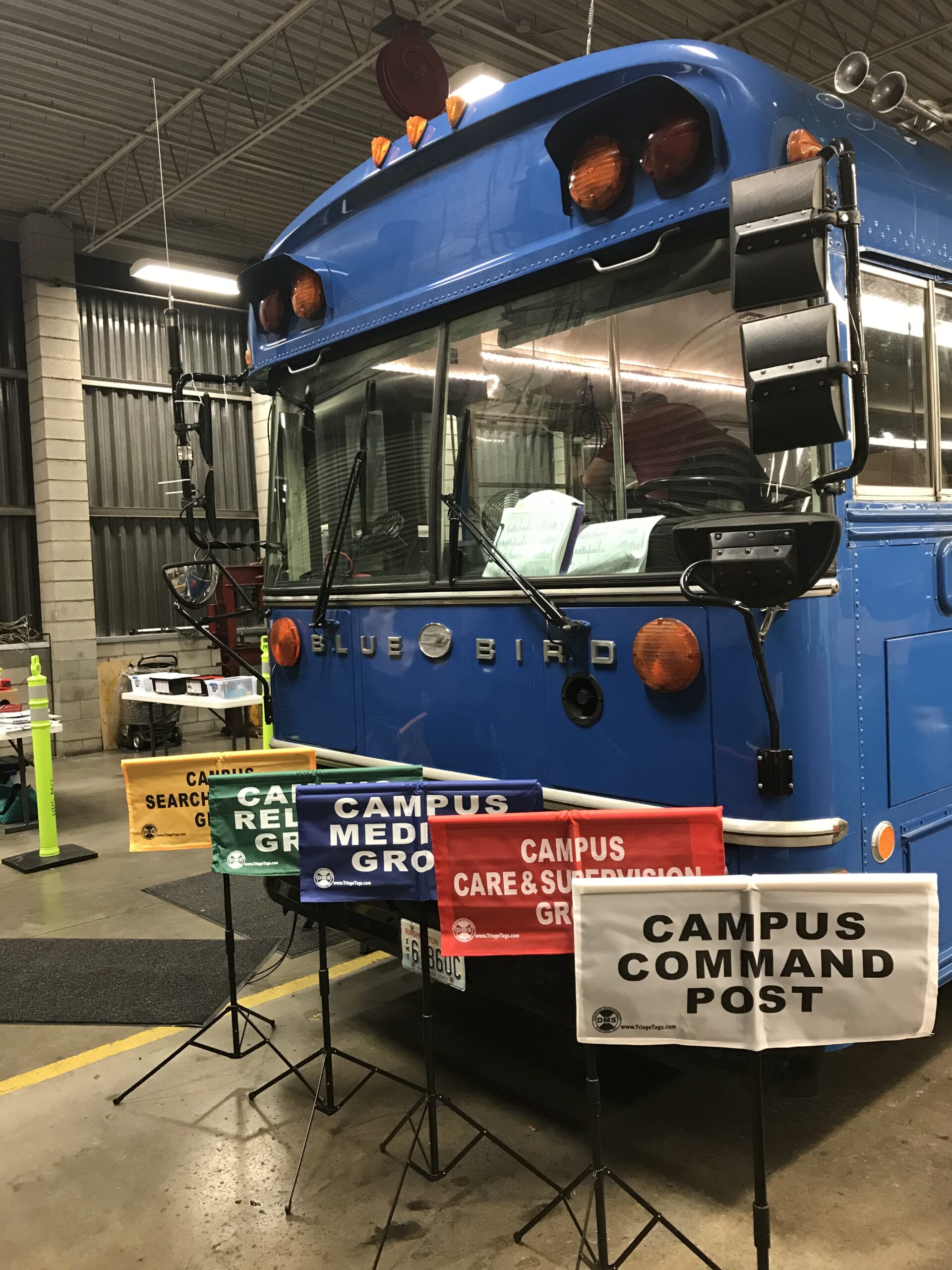

Inspired by a friend who was studying for the first exam, Mark began a journey that along the way included three levels of licensure, 28 FEMA certifications, and a snub-nosed school bus that would become a true Mobile Emergency Operations Center.

“Immediately, I saw the connection at the office, so I took a 50-foot, 85-passenger school bus and gutted it, then rebuilt it from the ground up.”

Ham radio inspired Mark Finstrom to transform an 85-passenger bus into a fully loaded mobile emergency ops center.

“It has fold-up desks in there, it’s fully carpeted, it’s got a 65-inch LED, four ham radios, police band, fire band, and then transportation and administrative bands for the district,” he said. “It’s totally self-sufficient, with two generators and internet via Cradlepoint hotspot. It’s got a weather station; it has high-def video cameras.”

In the belly of the bus live a vast array of emergency supplies — think 1,500 K95 masks, 10,000 gloves, laminated instructions that outline all CERT (certified emergency response team) roles. In the event of a disaster, Mark can assume any role, though he’s usually second-in-command after Scott Logan, the COO of the district.

“I can light up a football field with that bus,” Mark said.

All together, he said, the bus cost him about $50,000 to equip, and also serves as a mobile STEAM lab with 15 stations for elementary schools in the district. When it’s heading out to kids, some of the emergency supplies are replaced with big dry-tubs of instructional materials.

When used in an emergency, there is space for 12 to work inside the bus. As a mobile STEAM lab, there’s room for 15 kids to learn.

Then, there’s his personal equipment.

“I started with a BaoFeng uv-5r for $39,” he said. “Now, I have radios that range from the BaoFeng’s $39 up to $2,000.

“There are two in my vehicle at all times; one is mounted and one is not, and I have a ham radio in my office, at school and at home,” he said.

The bus is fully equipped for communication, including four ham radios, a J-pole and multi-function antenna tower, two 900Mhz radios, an 800Mhz radio, multi-carrier Cradle Point Access Point, cell carrier hotspots and more.

Both Josh and Mark emphasized that it’s not tough to get your start in ham radio. The initial license is easy to get — people have been known to pass the test using flashcards and just a few study sessions. There are also “cram and pass days” with local clubs, which is a one-day workshop with the test at the end.

“There are lots of free apps that help people study, and the questions in the apps are the actual bank of questions that are selected from,” Josh said. “And, of course, there are some great series on YouTube. Don’t be too daunted.”

Resources:

Ham Connections and Callsigns:

- Josh Kesecker: KG7JK, blogs at joshnmore.wordpress.com; coverage of his last dogsled race here

- ‘Mark Finstrom: KG7KAW

- Newberg Schools Superintendent Joe Morelock: K0LRM